by Elizabeth Phelps

Part 1: My New Puppy

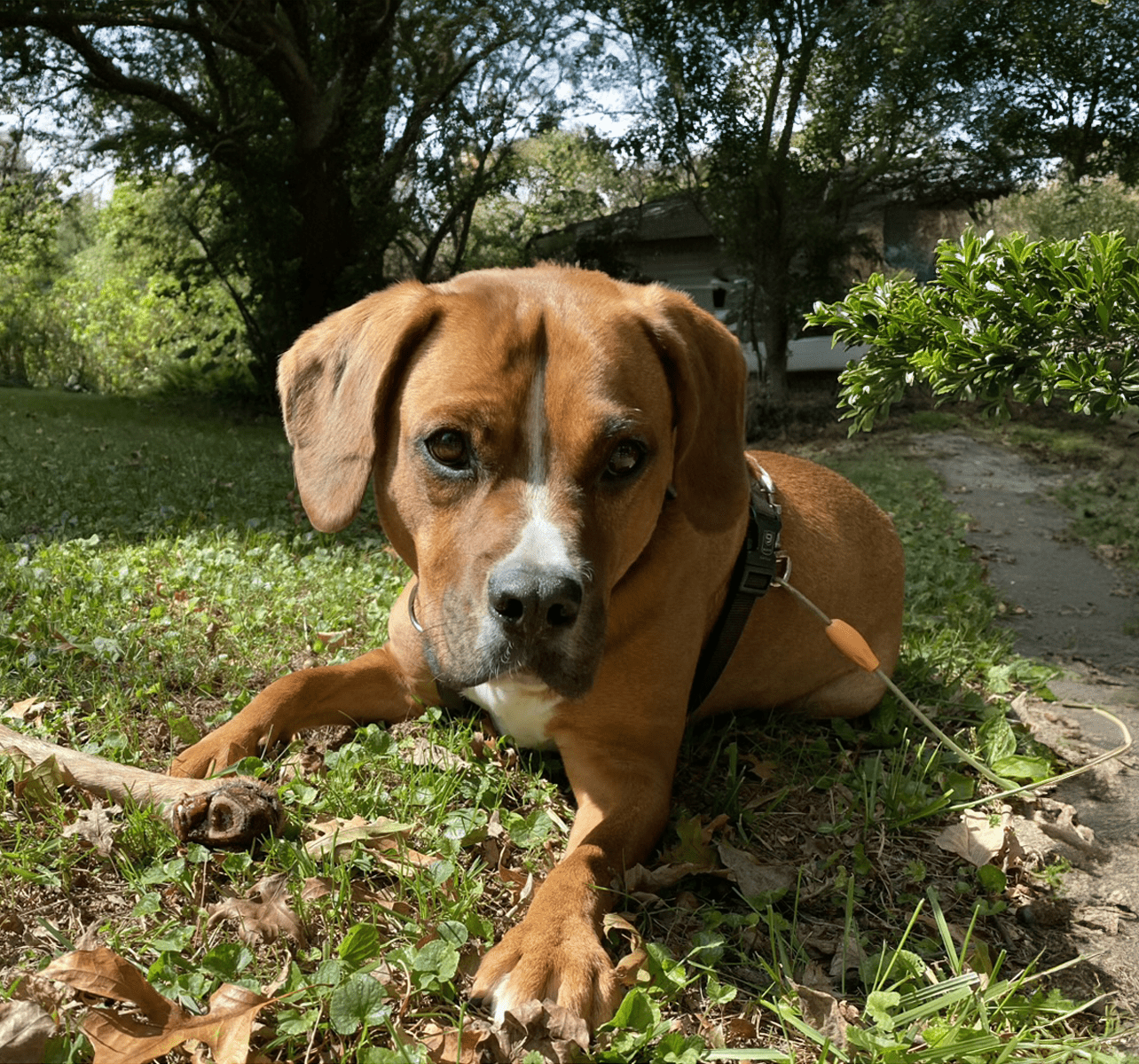

I brought Roscoe home from a local farmer's market when he was just 8-weeks old because I fell in love with his beautiful ears. The farm family that raised him is known for their attentive care of both their animals and their children, and they assured me of his good upbringing and socialization. Roscoe, a Staffordshire/Cavalier mix, had the robust build of a Staffy blended with the gentle disposition of a Cavalier. Although they estimated he would grow to about 30 lbs, a bit on the large side for us, we were excited to welcome him into our family.

As a puppy, Roscoe was incredibly sweet and playful, quickly adapting to his new home and remarkably compliant—he was already housebroken and showed no interest in chewing on inappropriate items. His intelligence and eagerness to please made basic obedience training a joy, and we both delighted in that time together. His love of car rides meant he was a constant companion, charming everyone he met with his soft, sweet nature.

However, as Roscoe grew, so did his anxieties. Initially a carefree pup, he increasingly exhibited signs of stress, guarding his food and acting aggressively towards other dogs. He became hypersensitive to any new stimulus; unfamiliar sounds, movements, or objects would send him into a state of panic, marked by frantic and relentless barking that affected the entire household. Roscoe's body grew to 60 lbs of muscle and, despite his gentle soul, his fear governed him, making him react explosively to the smallest changes.

This overwhelming fear made daily activities a challenge, as he was difficult to control on a leash and became too anxious to engage in public settings or continue his puppy play dates. The household revolved around managing his reactions, leaving me feeling stressed and helpless, constantly discouraged about others' perceptions of my sweet pup as a "bad" dog.

At the one-year mark, in a particularly distressing incident, Roscoe unexpectedly lashed out in fear and hurt Matilda, my son's mini-dachshund who lived with us and whom he trusted implicitly, signaling the need for professional help. They had been inseparable playmates, and this act of aggression was a clear sign that we had to intervene to help Roscoe manage his anxiety.

Part 2: Interventions and Discovering Agility

Determined to understand and help Roscoe, I sought the expertise of a professional dog trainer. The trainer quickly discerned that Roscoe's aggressive responses were manifestations of deep-seated fear rather than intrinsic aggression. Through careful observation and guidance, I learned to read his body language and recognize his stress signals, a crucial step in managing his triggers. The trainer taught us various de-escalation techniques and the importance of timely intervention to prevent situations from escalating.

Our sessions included targeted exercises, activities, and mental stimulation, designed not only to tire him out but also to engage him positively. We worked with Roscoe both individually and alongside Matilda, ensuring that their interactions remained safe and constructive. Despite our progress, the underlying anxiety persisted, limiting our activities and leaving both Roscoe and me on constant alert.

On the trainer's advice, we ventured into the world of dog agility. This provided Roscoe with a structured outlet for his energy and a controlled environment to safely encounter new stimuli and other dogs. Agility quickly became the highlight of our week; Roscoe excelled in the course, and it was heartening to see him enjoy himself. At the dog gym, trainers recognized him as "Highly Reactive," a new term for us, which led to our participation in reactivity classes. These classes were transformative, offering more in-depth strategies for desensitization, safe exposure to triggers, and redirection. I also learned techniques such as massage and began administering anxiety medications, which together helped us manage his stress more effectively.

Despite these interventions, Roscoe's ability to relax and play freely was still hindered by his constant anxious vigilance. It became clear that while we had made significant strides in managing his behavior, achieving true happiness for Roscoe required further exploration and adaptation of our approaches. Thus began our deeper journey into understanding and communicating with Roscoe, not just to manage his reactivity but to fundamentally improve his quality of life.

Part 3: Communicating Through Buttons

I first enrolled in the "Button Bootcamp," a foundational course that opened our eyes to the possibilities of communication through buttons. This course set the stage for a deeper exploration of how Roscoe could express himself beyond basic needs.

Encouraged by our initial progress, we advanced to the Let's Get Them Pressing course, a six-week program that proved to be a game-changer. The course was structured to provide detailed insights, personalized attention, and encouragement from the instructor. During this time, we delved into the nuances of how Roscoe was using the buttons and why. Initially I used narration as a way to communicate with him, but we discovered that it was actually serving multiple purposes—it acknowledged his feelings, provided comfort and reassurance, and acted as a de-escalation tool. This realization was pivotal; rather than continuously intervening, I was aiding Roscoe in articulating his emotions.

To enhance his communication, we introduced new buttons like "Happy" to offer a counterbalance to "Worried," as well as "Safe," a concept I had already been verbally reinforcing. "Check" was added to empower him to investigate his fears rather than react instinctively. This approach marked significant progress in giving Roscoe a sense of agency—something that had inadvertently been diminished through our earlier interactions, where his reliance on my direction was paramount.

The culmination of these classes saw Roscoe confidently using the buttons not just with me but also with my husband and other familiar people, though I needed to be in his line of sight. He learned to self-interrupt his overwhelming emotions by using the "Check" button to ask for help assessing whether a situation was genuinely threatening, progressing from repeatedly pressing "Worried" to asking if he was "Safe," to frequently expressing that he felt "Happy."

As Roscoe became more secure and less anxious, we noticed a decrease in his use of the buttons. There were moments when we would both pause at the communication board, unsure of what he wanted to convey. Despite having buttons that represented all his daily needs, activities, and fears, it seemed he was sometimes at a loss for how to express more complex thoughts or feelings.

This led us to the Advanced Button Teaching class where we introduced concepts like "Want," "Yes," and "No." Roscoe immediately took to these new options, often pressing "Want/Yes" and then looking at me expectantly, as if asking for help to clarify his desires. This interaction opened a new chapter in our communication, highlighting that while he knew he wanted something, he couldn't always pinpoint what it was, but he could ask for help to figure it out.

Today, Roscoe is a complex individual with deep thoughts and intense feelings. While he may never casually use the buttons like some dogs, the ability to communicate through this method has been transformative. It has built his confidence, given him a sense of agency, reduced our collective anxiety, and restored a semblance of normalcy to our household. Through assisted intercommunication (AIC), we have gained invaluable insights into his mental and emotional needs, enabling us to address them more effectively.

Roscoe's daily life has dramatically improved; he's more engaged, happier, and has resumed playing. He experiences anxious moments less frequently and no longer lives in a state of constant alertness. This journey with Roscoe has not just changed his life; it has enriched ours, deepening our bond and our understanding in ways we never imagined possible.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.